In

my previous post When Rhine and Pearce Got Smoking Gun Evidence

for ESP, I discussed a series of tests that provide very good

evidence for ESP (extrasensory perception). In 2013 this evidence and

other evidence for ESP was attacked in a book by Brian Clegg entitled

Extra Sensory. Although Clegg claims in the last paragraph of

this book that he was examining the topic of ESP “with an open

mind,” his complete hostility toward the topic is made clear

throughout his very jaundiced book, which is very much a one-sided

tract. Let's take a look at Clegg's attack, and see whether it has

any weight.

First,

let me describe the experiments with Hubert E. Pearce Jr., which were

performed at the prestigious Duke University during the 1930's, under

the supervision of Professor Joseph Rhine. The main series of tests

were tests not of telepathy (also known as mind-reading), but tests

of clairvoyance, an ability of a single mind to obtain information

through non-sensory means. Both telepathy and clairvoyance fall under

the category of ESP or extrasensory perception, since they would seem

to involve some kind of anomalous perception that does not involve

the senses.

The

clairvoyance tests done with Pearce (described here) were simple. Two people

would sit at a table, the person being tested, and an observer.

Twelve decks of cards were put on the table, cards known as Zener

cards, that can have one of 5 different symbols on one side (with all

the cards having the same appearance on the opposite side).

The person being tested would shuffle the cards, and the observer would then cut the cards, assuring that the top cards were random. The person being tested would then hold a series of cards (either 5 or 25) one by one, face down, and guess which of the five symbols was on the unseen side of the card. After the series was done there would then be a stack of either 5 or 25 cards which had been the target of guesses. Those cards would then be turned face up one by one. As each card was turned face up, the observer would record whether the previous guess about that card's symbol was correct or not correct.

Zener cards used in ESP testing

The person being tested would shuffle the cards, and the observer would then cut the cards, assuring that the top cards were random. The person being tested would then hold a series of cards (either 5 or 25) one by one, face down, and guess which of the five symbols was on the unseen side of the card. After the series was done there would then be a stack of either 5 or 25 cards which had been the target of guesses. Those cards would then be turned face up one by one. As each card was turned face up, the observer would record whether the previous guess about that card's symbol was correct or not correct.

With

a variety of observers and with a variety of testing conditions (some

of which would have absolutely precluded the possibility of

cheating), Hubert Pearce got astonishing results too good to be

explained by chance. Below is the result of these tests. These are tests in which the expected chance result (average per 25) is only 5.

Pearce

got 3746 correct guesses out of 10,300. We can use the very handy

binomial probability calculator at this

site to calculate the likelihood of these results. The calculator

gives a probability of simply 0 when we type in the overall results,

so let's use a subset to try to get some non-zero result. Let's use

only rows 2 and 6, involving either Pearce looking away from the

cards or a screen between Pearce and the cards, either one of which

should have ruled out any possibility of cheating. When I type these

results in the binomial probability calculator, I get a result with a

chance probability of 5 chances in 100 trillion, which we can round

to be 1 chance in 10 trillion. This is a result we should never

expect to get by pure chance even if we tested with every single

person in the human race.

Now

what does Clegg say to try to discredit this very convincing evidence

for ESP? For one thing, he suggests that Pearce may have got his

result by looking at cards seen in someone's glasses. This is a

completely illegitimate explanation for any of the results involving

Pearce. None of the results (neither the results discussed above, nor

the equally dramatic Pearce-Pratt experiment described below)

involved one person holding cards while looking at them while someone

nearby tried to guess the cards.

Pearce

was never trained in magic, and was never caught cheating during any

of the long series of tests he was involved which, which dragged on for

months. But this does not stop Clegg from offering the suggestion

that Pearce's incredible results were the result of cheating by him.

Clegg states, “I can think of three or four ways to do this, the

most obvious being to sneak a peek at an upcoming card when the

observer was concentrating on recording the previous guess.”

Clegg's

absurd reasoning here is wholly without merit. If one person is

sitting directly across a table from another person, and the second

person is taking a second to write down which of five guesses was

made (which almost certainly would take no more than a few seconds, since

it can be done by a one-letter notation), the first person would have

a very high chance of being detected any particular time that he

tried to peek at the top value of a card deck lying on the table.

This is because humans have peripheral vision. If you are writing a

one-letter jot on a piece of paper on a table, you can certainly see

in the “corner of your eye” with your peripheral vision someone

reaching out his hand to peek at the top card in a deck. I may also note that the

type of cards used here (Zener cards) don't even have an indication

of their value on their corner (unlike playing cards). So you can't

peek at the value of a Zener card just by turning its corner – you

have to flip the card over or half-turn the card.

But

in order for Pearce to have got the results that Rhine recorded, he

would have had to peek at the value of the cards hundreds of

times without ever being detected once by an observer sitting right

across from him (and have this happen with a number of different

observers). Under such conditions there is no chance that someone

would be able to successfully peek at the top value more than about

10 times without being detected, and it is very likely that the first

such attempt would be detected.

Another

reason why Clegg's reasoning is completely without substance is that

the table above shows that Pearce got extremely compelling results

even in 3 series in which there was zero chance of peeking, one in

which he was forced to look away from the observer, and two others in

which there was a screen between the cards and Pearce's face. In the

two “looking away” series (series 2 and 3 above) he got a total 515 successes out of 1125 (a result which there is basically zero chance of you getting by mere chance). In the two “screen between the cards and the card

guesser” tests the results were 215 correct guesses out of 600,

which has a probability of less than 1 in 10 trillion (1 in

10,000,000,000,000) according to the binomial calculator I just linked to.

Clegg

also suggests (without any evidence) that Pearce may have somehow made markings on the cards

allowing him to cheat. This extremely implausible suggestion is also without merit, as

Rhine's original account of the tests states, “We brought in new

cards many times, without there resulting any change in the level of

scoring.” The fact that 12 decks of cards were on the table for the

tests also means that card markings cannot explain the results. Clegg

also suggests that Pearce “had the opportunity to take a quick look

at the whole pack while not being observed.” This suggestion is

also without merit because the protocol involved cards that were

shuffled and cut before anyone guessed about their value.

Having

discussed the Pearce-Rhine clairvoyance tests, and having offered no

objections with any substance, Clegg goes on to discuss the equally

compelling Pratt-Pearce tests on telepathy. The format for these

tests was very different. A person called the observer (Professor

Pratt) shuffled a deck of Zener cards, and at particular intervals

would turn the top card and record its value. The person being tested

(Pearce) was in distant location 100 yards away or even farther

away. The person being tested had instructions to begin guessing

which card had been turned, beginning at a particular time known to

both the observer and the person being tested. After a particular

length of time had passed, both the observer and the person being

tested would hand in their written results to a third person, who

would check and see how many of the guesses were accurate.

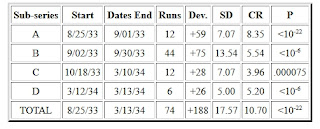

The tests (described here) were run from August 1933 to March 1934, totaling 74 runs

through a pack of 25 cards. The rate of card guessing was 1 per

minute. The total amount of time that Pearce spent guessing cards was

about 30 hours. 1850

cards were dealt, and the expected chance success rate was about 370

cards. Instead, Pearce got 558 correct guesses.

The

results of the test are shown below. The final column P shows the

probability of getting these result by chance, which was about 1 in

1022 or 1 in 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

To

try to debunk this result, Clegg suggests the idea that Pearce

secretly sneaked over to Pratt's office, and then peeked over a crack

at the top of the door. He restates an old idea that Pearce may have

peeked through a transom at the top of Pratt's office. This

suggestion is not at all credible for several reasons. For one thing,

there's a 99% likelihood that no one would ever attempt so risky a

procedure. Then there's the 99% likelihood that if someone did

attempt such a procedure, he would have been detected by Pratt (or by

Rhine, who joined Pratt for one of the series). If you are close

enough to see the values of cards being turned by peeking through a

transom, you are close enough to be heard or seen by the person

turning those cards (partially because standing on a chair for long

periods inevitably results in chair squeaks that can be heard). Then

there's the fact that if you were to spend hours peeking through a

transom at the top of a door (which would require standing on a

chair), there's a 99.9% likelihood that you would be detected by some

passerby, who would either report this suspicious behavior to the

professor, or ask aloud “why are you peeking through that transom,”

which would give you away (the halls of universities tend to have

lots of foot traffic at all hours of the day). So this transom

objection is not a reasonable reason for rejecting the Pearce-Pratt

result as being convincing evidence for ESP.

The

dismal failure of Clegg's debunking efforts can be shown as follows:

suppose we accept both this enormously implausible “transom

peeking” idea and also the infinitely more implausible idea of

hundreds of card deck peeks going unnoticed by an observer directly

across the table (which is rather like assuming that someone can

really jump to the moon). Then you still have not explained

away the evidence for ESP involving tests with Pearce – for even

then you still have no explanations for the extremely compelling

evidence produced when there was a screen between the card guesser

and the cards (series 6 listed in the first table) – tests in which

there were 215 correct guesses out of 600, which has a probability of

less than 1 in 10 trillion (1 in 10,000,000,000,000).

The

evidence discussed here involving Hubert Pearce is only one piece of

a great mountain of evidence showing the reality of ESP. Another

very important piece is the ganzfeld studies done in recent decades.

Repeated many times by many experimenters, these studies have

consistently shown that subjects undergoing sensory deprivation are

able to score at a rate of between 30% and 32% on tests in which the

chance result should only be 25%. This is overwhelming evidence for

ESP.

Clegg

is not able to debunk this evidence. His approach is basically to

look for anything at all which he regards as a discrepancy between

the way he would ideally do such a test, and the way the test was done, and to call that an error. The same type of reasoning might

lead someone to say that your SAT score is not reliable because there

was the “error” that there were not steel walls between yourself

and the test takers to your right and left.

Clegg

concentrates on mentioning issues with the early versions of the

ganzfeld experients. But the designers of these experiments closely

worked with skeptics, and came up with a joint statement agreeing on

protocols that should be followed henceforward to assure the

reliability of these experiments. Even after these tightened-up

protocols were put in place, the experiments continued to get results

showing dramatic evidence of ESP, with the subjects achieving

success rates between 30% and 32% far in excess of the 25% success

rate they should be getting if ESP does not exist. As wikipedia.com

reports, “In 2010, Lance Storm, Patrizio Tressoldi, and Lorenzo Di

Risio analyzed 29 ganzfeld studies from 1997 to 2008. Of the 1,498

trials, 483 produced hits, corresponding to a hit rate of 32.2%.”

That is a rate far above the expected chance rate of 25%. See the pdf here for a meta analysis reporting the 30% number.

Contrary

to the impression Clegg tries to create in his 2013 book (with some

blatant cherry-picking that omits results after the year 2000), the

spectacular success of the ganzfeld experiments have continued even

after the procedures had their protocols tightened-up. These recent

tests between 1997 and 2014 provide very good evidence for ESP, as

the likelihood of you getting these results by chance is much less

than 1 in a trillion. Why is it that Clegg takes five pages to

discuss the ganzfeld experiments, without taking a sentence to state

the results they got (a sentence like this: the chance expectation

was 25%, but the results were between 30 and 32%)? It's kind of like

someone arguing that Ty Cobb was a poor hitter, and conveniently

failing to mention Cobb's batting average.

The

evidence for ESP is overwhelming, and continues to accumulate. This

evidence holds up very well to Clegg's unsound assault, which

consists mainly of the noise of blank shells firing. Besides abundant

anecdotal evidence that frequently crops up in human experience (such

as when we think of someone who rarely calls on the phone, just

before he calls on the phone), there is over 100 years of compelling

published scientific evidence, involving a very large number of

subjects. At last year's conference of the Parapsychological Association, Dr. Diane Hennacy Powell presented a paper describing a

test with an autistic child, a subject producing results as

spectacular as those produced by Pearce in the 1930's. As discussed here, she showed a

long tape of an experiment with this subject at the conference, one

demonstrating spectacular results. As discussed here, she is currently working on a more

polished film that will present these results to the general public. A preliminary video of previous experiments with this autistic child can be seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment