Scientists

study the laws of nature in great detail, but it is relatively rare

for anyone to attempt a qualitative assessment of the laws of nature.

We might do such a thing by imagining three different quality

categories. If a law of nature seems to serve a good purpose, we

might call that law quasi-teleological, a term that means “as if it

was intended for a purpose.” If a law of nature seems to serve a

bad purpose, we might call it dysteleological, a term that means “as

if it was intended for a bad purpose.” If a law of nature seems to

serve no purpose either good or bad, we can simply call it neutral.

Let

us attempt to judge whether the most important laws of nature fall

into any of these three categories. One way to do that it is to make

judgments based on random incidents, or incidents chosen to support a

particular viewpoint. You would be following that approach if you

made statements like this:

I was hiking yesterday in the mountains, and hurt my leg when I slipped and fell. Damn that stupid law of gravity! It's such a terrible law.

Making

assessments of laws of nature based on incidental experiences such as

this does not make any sense. What we need is an intelligent

general-purpose algorithm for assessing whether a law of nature is

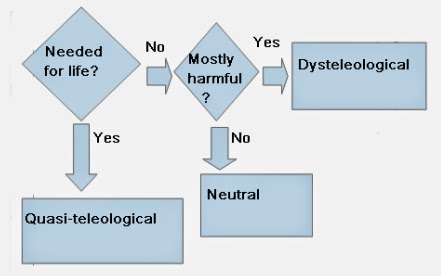

quasi-teleological, neutral, or dysteleological. I propose the

algorithm shown in the flowchart below.

The

algorithm starts by asking: is the law of nature necessary (directly

or indirectly) for the existence of living things such as ourselves?

If the answer to question is “Yes,” the law is considered

quasi-teleological, because it helps to achieve a good purpose (the

purpose of allowing creatures such as us to exist). If the answer is

“No,” the algorithm then asks whether the law of nature is mostly

harmful in its effects. If the answer to that second question is

“Yes,” the law of nature should be considered dysteleological (a

law that serves a bad purpose). If the answer to that question is

“No,” the law is considered to be neutral (meaning that it

neither seems to serve a good purpose, nor seems to serve a bad

purpose).

Let's

try a simple example, and see whether the algorithm seems to make

sense. Consider the case of the law of gravitation, the universal law

of nature that there is a force of attraction between all massive

bodies, directly proportional to the product of their masses, and

inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Gravitation is (indirectly) absolutely necessary for the existence of

living beings, because if it were not for gravitation we would have

neither a planet to live on, nor a sun to produce warmth. So even

though occasionally gravity produces deaths from falling, the fact

that gravitation is absolutely necessary for planets decisively

trumps all other considerations. It is therefore absolutely correct

for us to consider gravitation as a quasi-teleological law. It serves

the good purpose of allowing the existence of planets for living

things to exist on. In this case the algorithm seems to steer us to

the right answer.

Let

us apply the same algorithm to other major laws of nature. Another

major law of nature is Coulomb's law (the basic law of

electromagnetism). This is the law that between all electrical

charges there is a force of attraction or repulsion, directly

proportional to the product of their charges, and inversely

proportional to the square of the distance between them. It is true

that very rarely this law helps to kill people in lightning strikes,

but that fact is absolutely trumped by the fact that living things

could not exist for even a minute without Coulomb's law.

Electromagnetism is what makes chemistry possible, and without

chemistry we would all instantly die. If you were to turn off

Coulomb's law, our bodies would quickly disintegrate. So again, using

the above algorithm, we must classify Coulomb's law as a

quasi-teleological law, as it serves the good purpose of allowing the

existence of biological organisms.

The

table below shows a list of fundamental laws of nature. Most of the

laws have commonly used names, but some very important laws do not

have any common name, although they should have one. One of the most

important laws is one I have designated below as the Law of the Five

Allowed Stable Particles. This is simply the law that rather than

producing hundreds or thousands of different types of stable

particles from a high-energy particle collision, nature makes sure

that only five types of stable particles result. Although not

important now, the current arrangement of matter in the universe

would be hopelessly different (in a very negative way) if such a law

had not applied shortly after the Big Bang, when all the particles in

the universe were colliding together at high speeds. You can say the

same about the other conservation laws listed below.

All

of these laws have one thing in common: for various reasons, all of

them are necessary for the existence of life. In the case of the law

of the strong nuclear force, the Pauli exclusion principle, and the

law of electromagnetism, this is glaringly obvious, as we couldn't

exist for even a minute if these laws didn't exist. In the case of

the law of gravitation, it's almost as obvious that it is required

for life, as gravitation is absolutely necessary for the existence of

planets. In the case of the law of the conservation of baryon number,

this college physics textbook says, “if it were not for the law of

the conservation of baryon number, a proton could decay into a

positron and a neutral pion.” If such a decay were possible, there

wouldn't be any protons around by now, nor would there be any life.

In

the case of the law of the conservation of charge, the law guarantees

that electrons are stable particles that cannot decay into neutrinos,

and thereby assures that we have a universe with plenty of the

electrons needed for atoms and life. In the case of the laws of

quantum mechanics, we have laws that restrict the states that

electrons can take inside an atom, and thereby prevent electrons from

falling into the nucleus of an atom (something they would otherwise

have a strong tendency to do because of the very strong

electromagnetic attraction between protons and electrons).

As

all of these laws are needed for life, we must characterize all of

them as quasi-teleological. But

other laws of nature should be classified as neutral, because they do

not seem to have any bad effect nor any good effect.

Although the modern materialist scientist may attempt to banish teleology from nature, such an attempt is not at all supported by his subject matter. The quasi-teleological nature of the main laws of nature present a huge problem for those who wish to believe in a capricious universe whose characteristics are the result of blind chance. Such people have not only the huge problem of explaining the universe's fine-tuned fundamental constants, but also the problem of explaining the universe's fine-tuned laws.

Although the modern materialist scientist may attempt to banish teleology from nature, such an attempt is not at all supported by his subject matter. The quasi-teleological nature of the main laws of nature present a huge problem for those who wish to believe in a capricious universe whose characteristics are the result of blind chance. Such people have not only the huge problem of explaining the universe's fine-tuned fundamental constants, but also the problem of explaining the universe's fine-tuned laws.

No comments:

Post a Comment